Conservation

“Wherever humans have settled islands, they have introduced plants and animals. Lord Howe Island is no exception.”

Early sailors put pigs and goats onto the island for food; the settlers brought farm animals (cattle and horses) and domestic animals (cats and dogs.) The worst feral mammal to arrive was the Black rat, Rattus rattus, that got onto the island in 1918 with an incident involving the cargo ship Makambo. Some of the plants humans brought over for food, or garden ornamentals, had spread into the native forest and are classed as weeds.

The Woodhen

As part of the rescue program, funding of $250,000 was raised by the newly formed National Parks Foundation and a captive breeding program was carried out on the island. Three pairs of Woodhens were whisked off the summit of Mount Gower by helicopter, to a breeding facility built for the purpose. New Zealander bird breeder Glen Fraser looked after the Woodhen pairs, and helped them raise 93 Woodhens that were released around the island. With the environment now predator-free the Woodhens quickly began breeding with the others left in the wild, and after five years the population of Woodhens had grown to about 280. At the time this was the most successful captive bird breeding program in the world.

Goats

In 1999 a team of New Zealand hunters was employed to remove wild goats that had also been put on the island by early sailors. Over a three-month period, the team, with locals, removed 384 goats.

The recovery in plant life has been remarkable since these browsing goats have been removed.

Rodents

In 2002 the Lord Howe Island Board began investigating the feasibility of removing rodents from the island. At the time, techniques had been developed to do this on islands around the world, led by Department of Conservation in New Zealand.

Over the next seven years a draft plan was prepared to carry out a rodent eradication on Lord Howe Island, using the experience and science from what had been achieved around the world since 1980 when the process was pioneered. Funding for the Lord Howe Island project was received from State and Federal governments in 2012, and over the next seven years the plan was fine tuned.

In 2019 the Rodent Eradication Project was carried out. The plan was designed to ensure every rat and every mouse on the island received a bait pellet containing the anticoagulant Brodifacoum.

In the settlement area small bait stations were laid out on a ten-metre grid across the ground by a team of 50. Smaller mouse bait stations were placed in all buildings across the settlement. These were topped up with baits once a week for two months.

The rugged mountain and cliff areas away from the settlement had bait pellets carefully delivered by helicopters, in two bait drops, two weeks apart. Dogs trained to detect rodents were brought over to search for any remaining rodents.

The last live rodent was found in September 2019. The program will be officially declared a success in October 2021 if no rodents are detected by then.

The benefits from these conservation programs are being monitored and significant increases in birds, invertebrates and plants species are being recorded.

Weeds

The Island has a very detailed Weed Eradication Program that was developed in the early 2000s. The Lord Howe Island Board has a Weed Team with locals, volunteers and mainland contractors employed in removal of noxious weeds. The system is based on the New Zealand Island model for weed eradication, where the island is divided into blocks. Funding is sourced to have the weed team sweep through each block systematically and remove weeds, recording effort, time, and weeds removed to keep track of progress. After nearly twenty years of this project some 90 percent of weeds have been removed, and helicopters are being used to ferry workers into remote mountain areas. Drone technology is also being investigated as a method for controlling weeds in more remote areas. See the Lord Howe Island Board website for updates: LHIB Weed Eradication Program

A volunteer group, the Friends of Lord Howe Island, runs a number of special weeding ecotours each year, combining weed removal and learning about the island on guided walks, contributing to the weed eradication program.

Other conservation activities

Future conservation plans will involve translocation of some invertebrates that survived on rodent-free offshore islets, such as the Lord Howe Island phasmid and a number of flightless beetles. There is a possibility of re-establishing lost land bird species with very similar subspecies of land birds from other Tasman Sea islands such as Norfolk Island.

Other conservation programs include Big Headed Ant eradication; a Biosecurity and Plant importation policy; and a Dog Importation and Management Policy. See the Lord Howe Island Board website for these and other conservation policies: LHI Board Environmental Programs

You may also be interested in…

Tourism on Lord Howe Island

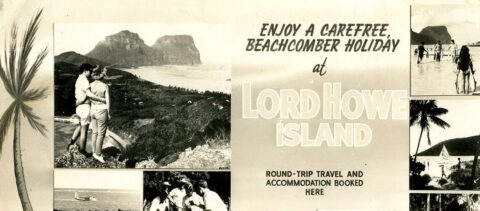

Tourism brochures on display at the museum reflect the evolving transportation, accommodation, and experiences on Lord Howe Island over time.

Sponsorship enables LED lights to be installed

Twent-five years after the building was constructed, new LED lights have been installed in all the museum rooms and exhibition areas.

The shipwreck of the SS Ovalau

Recently, the great-grandson of Captain Todd, master of the SS Ovalau shipwrecked in 1903, visited Lord Howe Island and related the story of his ancestor.

2024 Sea Slug Census

The seventh annual Sea Slug census was held on Lord Howe Island during February and March.