Phasmids

“The Lord Howe Island phasmid story.”

Dryococelus australis, commonly known as the Lord Howe Island phasmid or tree lobster, is a species of stick insect that lives on the Lord Howe Island Group. It is the only member of the monotypic genus Dryococelus and was thought to be extinct by 1930, only to be rediscovered in 1964 on a small nearby islet called Ball’s Pyramid.

It is no longer found on Lord Howe Island, and has been called “the rarest insect in the world”, as the rediscovered population consisted of only 24 individuals living on Ball’s Pyramid.

Adult Lord Howe Island stick insects can measure up to 20 centimetres in length and weigh 25 grams, with males 25% smaller than females. They are oblong in shape and have sturdy legs. Males have thicker thighs than females. Unlike most phasmids, they have no wings, but are able to run quickly.

The behaviour of this stick insect is highly unusual for an insect species, in that the males and females form a bond in some pairs. The females lay eggs while hanging from branches. Hatching can happen up to nine months later. The nymphs are first bright green and active during the day, but as they mature, they turn brown, then black and become nocturnal.

Reproduction can happen without the presence of males (parthenogenesis) – in which all hatched phasmids are females. This quality has allowed the species to survive when they are low in numbers.

The stick insects were once very common on Lord Howe Island, where they were used as bait in fishing. They were believed to have become extinct soon after the supply ship SS Makambo ran aground on the island in 1918, allowing black rats to become established.

After 1930, no stick insects could be found. However, in 1964, a team of climbers visiting Ball’s Pyramid, a rocky sea stack 23 kilometres south-east of Lord Howe Island, discovered a dead Lord Howe Island stick insect. During subsequent years, a few more recently-dead insects were discovered by climbers, but expeditions to find live specimens were unsuccessful.

In 2001, Australian scientists David Priddel and Nicholas Carlile hypothesised that there was sufficient vegetation on the islet to support a population of the insects, and, with two assistants, travelled there to investigate further. They scaled 120 metres of grassy, low-angled slope, but found only crickets. On their descent, the team discovered large insect droppings under a single Melaleuca shrub growing in a crevice approximately 100 metres above the shoreline. They deduced that they would need to return after dark, when the insects are active, to have the best chance of finding living specimens. Carlile returned with local ranger Dean Hiscox and, with a camera and flashlights, scrambled back up the slopes. They discovered a small population of 3 insects living beneath the Melaleuca shrub amongst a substantial build-up of plant debris. Another expedition the following year found 24 phasmids.

In 2003, a research team from New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service returned to Ball’s Pyramid and collected two breeding pairs, one destined for a private breeder in Sydney and the other sent to the Melbourne Zoo. After initial difficulties, the insects were successfully bred in captivity in Melbourne. The ultimate goal was to produce a large population for reintroduction to Lord Howe Island, providing that a project to eradicate the invasive rats was successful.

In 2006, the captive population of insects numbered about 50 individuals, with thousands of eggs still to hatch.

In 2008, when Jane Goodall visited the zoo, the population had grown to 11,376 eggs and 700 individuals, 20 of which were soon after returned to an enclosure on Lord Howe Island.

By April 2012, Melbourne Zoo had reportedly bred over 9,000 of the insects, including 1,000 adult insects, plus 20,000 eggs.

In 2014, an unauthorised climbing team sighted live stick insects near the summit of Ball’s Pyramid, in a thicket of sedge plants rooted in very thin soils at an altitude of 500 metres, suggesting that the insect’s range on the island is more widespread than previously thought, and that its food preferences are not limited to Melaleuca howeana.

By the beginning of 2016, Melbourne Zoo had hatched 13,000 eggs, and had also sent eggs to the Bristol Zoo in England, the San Diego Zoo in the United States, and the Toronto Zoo in Canada, to establish distinct insurance populations.

A 2017 study comparing DNA sequences of phasmids originating from Ball’s Pyramid with those from museum specimens from Lord Howe Island showed that the Ball’s Pyramid sequences differ from those of Lord Howe Island by a degree comparable to variation within the museum specimens, despite some morphological differences between the two groups. This confirmed that the two populations represent the same species.

In 2018 the plan to exterminate the black rat population on Lord Howe Island cited the reintroduction of the phasmid to the main island as a potential beneficial outcome.

Re-introduction of the phasmid

The Rodent Eradication Plan for Lord Howe Island was carried out in 2019. Plans to reintroduce the phasmid to the island will be undertaken very carefully, starting with a trial project to release a small number of phasmids onto Blackburn Island, within the Lagoon. In 2018 and 2019 revegetation projects began the restoration of this island with native plants that will be food for phasmids to be released in the trial. When these plants have grown to useful size, the trial will begin.

Saving Vanessa

In 2017, a daring Australian Museum expedition to Lord Howe Island succeeded in its search for the rare and elusive Lord Howe Island Phasmid.

Scientists and rock climbers collaborated in a project to survey the Pyramid and collect new phasmid specimens. The members of the rock climbing team were Paul Priebbenow, Zane Priebbenow, Vanessa Wills, Keith Bell, David Gray and Brian Mattick.

A new female phasmid (nick-named Vanessa) was recovered, adding genetic diversity to the breeding program at Melbourne Zoo, and in doing so increasing the chances of survival, and eventual return of the species to its native home on Lord Howe Island.

References

The text for this article has been adapted from several sources, including many Wikipedia entries. Some of the images have been sourced from Wikimedia Commons and are in the public domain. Wherever possible, the sources, artists or authors have been attributed above.

Additional reading:

VIP – Very Important Phasmid The Australian Museum Blog, May 2017

Dryococelus australis Wikipedia, July 2021

You may also be interested in…

Earth Day 2025

April 22nd is Earth Day 2025. We invite all e-bike owners on the island to meet at Signal Point for a group photo.

Visiting summer birds

In the summer on Lord Howe Island we see several birds visiting from the northern hemisphere.

50th Anniversary of the Airstrip

In early September, there were celebrations on the island to mark the 50th anniversary of the construction of the Lord Howe Island airstrip.

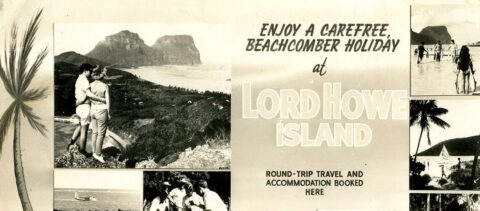

Tourism on Lord Howe Island

Tourism brochures on display at the museum reflect the evolving transportation, accommodation, and experiences on Lord Howe Island over time.