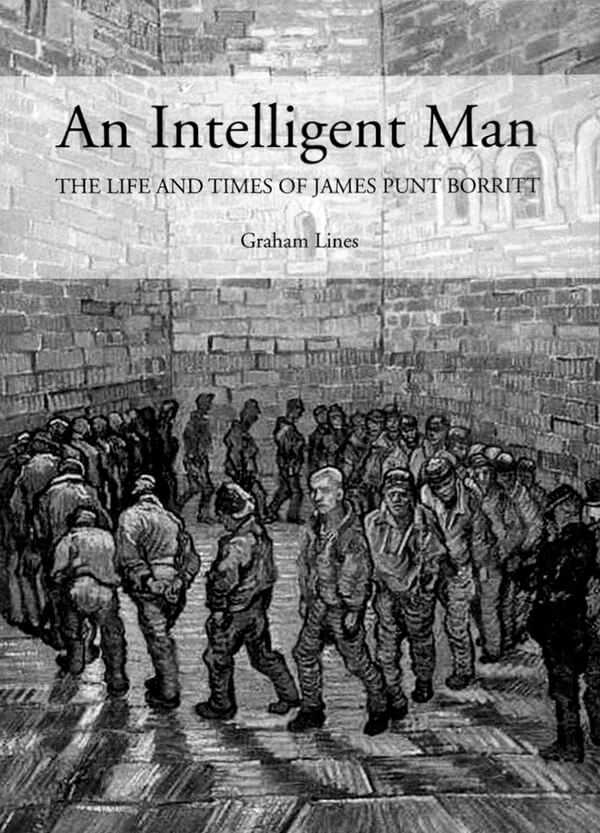

Just turned up in the post from the U.K. is a book from the author Graham Lines, about the life of a convict and a connection with Lord Howe Island.

James Punt Borritt was a convict who had been transported from England to Norfolk Island, where he and others escaped in a longboat, and spent 7 months on a remote island of New Hebrides group. They were picked up by a whaling boat and went to America, and eventually Borritt found his way back to England.

He was again apprehended and again transported to Norfolk Island, and then transferred to Van Diemen’s land, where he again escaped and once again ended up in England.

He was arrested again, but pardoned by Queen Victoria for saving a man’s life while in Australia.

Somewhere in this adventure he was on a whaling boat that stopped at Lord Howe Island in 1842. One of his companions wrote a vivid description of how the wild pigs were caught for food for the whalers.

James Punt Borritt is one of only two known convicts to have been transported three times. He was convicted and transported twice under that name and on a third occasion, under the name John Jones and sent to Fremantle, Western Australia.

Borritt‘s travels in the 1840s

”I was taken on board the Governor Halkett of Sydney, and at Howe’s Island joined the American whaler Benezet of Fairhaven.”

When Borritt handed his note to the judge at his Old Bailey trial in February 1852, it stated that: “I and two of my companions then embarked on board a whaler, leaving our companions behind.” Borritt never specified where he joined the Halkett. She was a whaler under Captain Joseph Bradley, out from its home port of Sydney since 31st January 1840.

This was almost four months before Borritt had even arrived on Norfolk Island. The length of a whaling voyage was determined by the success of the hunt, balanced against the determination of the master and his ability to keep a crew. What is clear is that some of Borritt’s group chose to remain [on Rotuma], implying levels of comfort, confidence and choice about which vessel they might take. The Rotuma Islands [where he and his companions had spent several days after surviving a murderous rampage by a runaway convict] would have fulfilled these criteria. Being as they were escaped convicts, joining the Halkett could result in finding themselves on Sydney’s streets as ‘wanted’ men.

Nevertheless Borritt and company were, it seems, sufficiently rested and keen to move on. At some point they would find another ship. It was the last occasion where Borritt refers to the other fugitives.

By curious chance we can state, with good evidence, precisely where Borritt was on the night of 24th March 1842. From the Sydney Herald for the 6th June, under the banner:

Howe’s Island Shipping: We have been favoured by Captain Poole with the following shipping intelligence… since January 8, 1842.

Poole had recently set up a provisions station on Lord Howe’s Island, situated about halfway between Sydney and Norfolk Island.

The whaling barque Governor Halkett, of Sydney, out twenty-six months, 900 barrels of sperm oil, Bradley, master, arrived on the 24th and sailed on the 25th March, 1842.

Crucially for this element of Borritt’s story the article also reported:

The barque Benezet, Parker, master, returned to the island on the 22nd March, and sailed 25th March, 1842.

As Borritt’s recent companions had probably feared, Captain Bradley had decided to head for home. Borritt would have been delighted to find the American whaler Benezet at anchor on arrival. He, no doubt, presented himself as an experienced seaman (and now whaler) to Captain Parker; with the prospect of an eventual voyage to her home port of Fairhaven, Massachusetts. In 1840 the United States of America existed westward only to the central plains; its ports all lay on the Atlantic coast. She had been out since December of that year.

Borritt’s professional seamanship, and recent whaleboat experience in the dangerous seas about Norfolk Island (and beyond) would have been an asset.

One of Borritt’s new American crew-mates was a young man about ten years his junior named George Runels. Decades later Runels wrote his life story, including details of the ‘whaling days’ of his youth.

On sighting a whale several boats would be deployed and the pursuit commenced; the object being to lance the beast from each boat and thereby slow the giant before the kill. Of course this was a perilous exercise for all concerned. Runels described one encounter during a hunt off Norfolk Island itself. A ship-mate having struck the animal, his boat was capsized; the man clinging on grimly –

the line had got a turn around his legs and took him down as near as we could judge, fully twenty fathoms and nothing but the whale’s rising to the surface saved him… it was three weeks before he could do anything… he was a Kanaker, and like a duck in water. The whale made 70 barrels of oil, about $3,000.

Hunting pigs on Lord Howe Island

Runels recalled how it worked for vessels calling at Lord Howe Island. Poole kept a pack of dogs there, and each vessel’s crew would use them to hunt the pigs that roamed freely. Crews would capture as many as required, then settle-up before rowing back to their ship. The dogs worked in pairs – catching a pig by the ears; whereupon the sailors would run up, cross his legs and bind them, then take a pole and carry him to the beach, then start again.

Runels’ ship worked in two gangs and caught 20 pigs that day. One afternoon they went fishing inside the island reef, and caught 10 or 12 ”salmon”. They also obtained sweet com, pumpkins, squashes, potatoes and the watermelons were very nice.

Further reading

The Police Magistrate’s Blog, January 28, 2020

James Punt Borritt (alias George Parker, John Jones, etc.) (c1814 – ?)

Harvey History online, October 12, 2020